Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of pancreatic cancer

Pancreatic Cancer

According to statistics in 2014, the estimated number of new cases of pancreatic cancer in developed countries (the United States) is ranked 10th for men and 9th for women, accounting for the fourth place in mortality from malignant tumors.

Pancreatic cancer is the seventh leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. However, its toll is higher in more developed countries. Reasons for vast differences in mortality rates of pancreatic cancer are not completely clear yet, but it may be due to lack of appropriate diagnosis, treatment and cataloging of cancer cases. Because patients seldom exhibit symptoms until an advanced stage of the disease, pancreatic cancer remains one of the most lethal malignant neoplasms that caused 432,242 new deaths in 2018 (GLOBOCAN 2018 estimates). Globally, 458,918 new cases of pancreatic cancer have been reported in 2018, and 355,317 new cases are estimated to occur until 2040. Despite advancements in the detection and management of pancreatic cancer, the 5-year survival rate still stands at 9% only. To date, the causes of pancreatic carcinoma are still insufficiently known, although certain risk factors have been identified, such as tobacco smoking, diabetes mellitus, obesity, dietary factors, alcohol abuse, age, ethnicity, family history and genetic factors, Helicobacter pylori infection, non-O blood group and chronic pancreatitis. In general population, screening of large groups is not considered useful to detect the disease at its early stage, although newer techniques and the screening of tightly targeted groups (especially of those with family history), are being evaluated. Primary prevention is considered of utmost importance. Up-to-date statistics on pancreatic cancer occurrence and outcome along with a better understanding of the etiology and identifying the causative risk factors are essential for the primary prevention of this disease.

Pancreatic cancer treatment guidelines

Recommendation level: Category1:

Supported by high-level evidence, all experts reach consensus recommendation;

Category2A: Supported by lower-level evidence, all experts reach consensus recommendation;

Category2B: Supported by lower-level evidence, some experts reach consensus recommendation;

Category3: any Supported by grade evidence, there is a big controversy. Unless otherwise marked, this guide is recommended for

Category2A level.

The diagnosis and treatment of pancreatic cancer is recommended to a larger-scale diagnosis and treatment center and carried out in the mode of multidisciplinary team (multidisciplinary team, MDT), including surgery, imaging, endoscopy, pathology, oncology, intervention, radiotherapy and other professionals. Participate and run through the entire process of patient diagnosis and treatment. According to the patient’s basic health status, clinical symptoms, tumor stage and pathological type, jointly formulate a treatment plan, personally apply multi-disciplinary and multiple treatment methods to enable the patient to achieve the best treatment effect. This guideline applies only to malignant tumors (pancreatic cancer) of pancreatic ductal epithelial origin.

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of pancreatic cancer

Risk factors for pancreatic cancer

Including smoking, obesity, alcoholism, chronic pancreatitis, etc., those exposed to naphthylamine and benzene compounds have a significantly increased risk of pancreatic cancer. Diabetes is one of the risk factors for pancreatic cancer, especially in elderly patients with low body mass index and no family history of diabetes. New type 2 diabetes should be followed up and alert to the possibility of pancreatic cancer.

Pancreatic cancer has a genetic susceptibility. About 10% of pancreatic cancer patients have a genetic background. Patients with hereditary pancreatitis, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, familial malignant melanoma, and other hereditary tumor disorders have a significant risk of pancreatic cancer increase.

Selection of diagnostic methods

The main symptoms of pancreatic cancer patients include upper abdominal discomfort, weight loss, nausea, jaundice, steatorrhea, and pain, which are not specific. For patients with clinically suspected pancreatic cancer and high-risk groups of pancreatic cancer, noninvasive examination methods should be preferred for screening, such as serological tumor markers, ultrasound, pancreatic CT or MRI. The combined detection of tumor markers and the combination of imaging examination results can increase the positive rate and contribute to the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of pancreatic cancer.

Evaluation criteria for resectable pancreatic cancer

In the MDT mode, the diagnosis and differential diagnosis are completed based on the patient’s age, general condition, clinical symptoms, comorbidities, serological and imaging examination results, and the resecibility of the lesion is evaluated.

Preoperative biliary drainage

Preoperative biliary drainage to relieve obstructive jaundice is controversial in terms of improving the patient’s liver function and reducing the perioperative complication rate and mortality rate. It is not recommended to perform routine biliary drainage before surgery. If the patient has fever and cholangitis and other infections, it is recommended to perform biliary drainage before surgery to control the infection and improve perioperative safety. According to the technical conditions, you can choose endoscopic transduodenal papillary stent or percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTCD). If the patient intends to undergo neoadjuvant therapy, patients with jaundice should also be placed in a stent to relieve jaundice before treatment. If the endoscope stent is for short-term drainage, it is recommended to insert a plastic stent.

PTCD or endoscopic stent placement can cause related complications. The former can cause bleeding, bile leakage, or infection, and the latter can cause acute pancreatitis or biliary tract infection. It is recommended to complete the above-mentioned diagnosis and treatment in a large-scale diagnosis and treatment center.

Scope of lymph node dissection for radical resection of pancreatic head cancer and pancreatic body and tail cancer

For the lymph node grouping of pancreatic cancer, the literature and guidelines at home and abroad mostly use the grouping of the Japanese Pancreas Society as the naming standard.

Judging criteria for cutting edge

In the past literature, the presence or absence of tumor cells on the surface of the margin was used as a criterion for judging R0 or R1 resection. Based on this standard, there was no statistically significant difference in the prognosis between R0 and R1 resection patients. R0 resection patients still had a higher local recurrence rate. It is recommended to judge whether R0 or R1 resection is based on the presence or absence of tumor infiltration within 1 mm from the cutting edge. If there is tumor cell infiltration within 1 mm from the cutting edge, it is R1 resection; if there is no tumor cell infiltration, it is R0 resection. Taking 1 mm as the judgment principle, the difference between the prognosis of R0 and R1 patients is statistically significant. Due to the anatomical location of pancreatic cancer and the adjacent relationship with the surrounding blood vessels, most patients with pancreatic cancer undergo R1 resection. If the cut edge is judged by the naked eye to be positive, it is R2 resection.

Standardization of pancreaticoduodenectomy specimens

Promote standardized testing of pancreaticoduodenectomy specimens. Under the premise of ensuring the integrity of the specimens, the surgical and pathological physicians cooperate to mark and describe the following cutting edges of the specimens to reflect objectively and accurately Cutting edge state.

Palliative care

The purpose of palliative treatment is to relieve biliary and digestive tract obstruction, improve

the quality of life of patients, and extend the life span. About two-thirds of pancreatic cancer patients have jaundice. For patients with unresectable and obstructive jaundice, pancreatic carcinoma of the duodenum papillary tract is used to relieve jaundice. Stents include metal and plastic stents The application can be selected according to the patient’s expected survival time and economic conditions. Patients with no pathological diagnosis can brush the pancreatic juice for cytological diagnosis. The incidence of blockage of plastic stents and induced cholangitis is higher than that of metal stents, which need to be removed and replaced. Patients with duodenal obstruction who cannot be placed endoscopically into the stent can be percutaneously transhepaticly punctured and placed outside of the catheter, or the drainage tube can be placed into the duodenum through the nipple. Into the duodenum to relieve gastrointestinal obstruction.

Postoperative adjuvant therapy

Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer has a definite effect in preventing or delaying tumor recurrence. Compared with the control group, it can significantly improve the prognosis of patients and should be actively implemented (Category 1). Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended for fluorouracil or gemcitabine monotherapy (Category 1). For patients with good physical fitness, combined chemotherapy can also be considered. Adjuvant therapy should be started as soon as possible, and 6 cycles of chemotherapy are recommended.

Treatment of unresectable locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer

For unresectable locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer, aggressive chemotherapy can help relieve symptoms, prolong survival, and improve quality of life. According to the patient’s physical condition, the options include: gemcitabine monotherapy (Category 1), fluorouracil monotherapy (Category 2B), gemcitabine-fluorouracil drugs (Category 1), gemcitabine + albumin-binding paclitaxel (Category 1), FOLFIRONO Scheme (Category 1), etc. Gemcitabine combined with molecular targeted therapy is also a viable option (Category 1). Those with tumor progression can still use alternative drugs such as oxaliplatin.

Follow-up of pancreatic cancer patients after surgery

Patients after resection should be followed up every 3 to 6 months within 2 years after the operation. Laboratory examinations include tumor markers, blood routine and biochemistry. Imaging examinations include ultrasound, X-ray and abdominal CT (Category) 2B).

Source: Western Cancer Information

- Alysha Mendossahttps://cancerfax.com/author/alysha/

- Alysha Mendossahttps://cancerfax.com/author/alysha/

- Alysha Mendossahttps://cancerfax.com/author/alysha/

- Alysha Mendossahttps://cancerfax.com/author/alysha/

Related Posts

- Comments Closed

- April 18th, 2020

- Datopotamab deruxtecan-dlnk is approved by the USFDA for EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer

- Tafasitamab-cxix is approved by the USFDA for relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma

- PiggyBac Transposon System: A Revolutionary Tool in Cancer Gene Therapy

- Breakthrough Treatments for Advanced Breast Cancer in 2025

- Neoadjuvant and adjuvant pembrolizumab is approved by the USFDA for resectable locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- Mitomycin intravesical solution is approved by the USFDA for recurrent low-grade intermediate-risk non-muscle invasive bladder cancer

- Taletrectinib is approved by the USFDA for ROS1-positive non-small cell lung cancer

- Darolutamide is approved by the USFDA for metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer

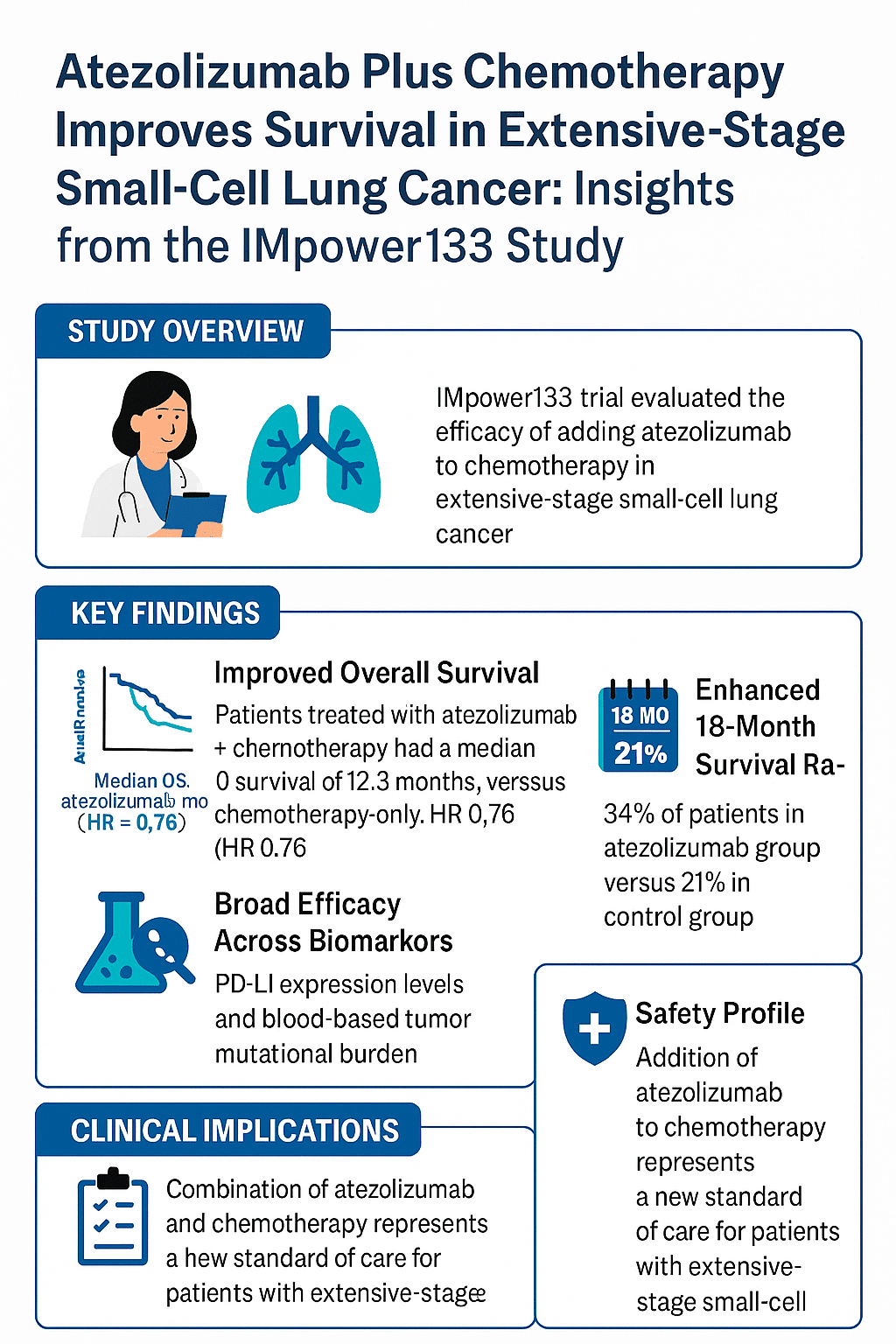

- Atezolizumab Plus Chemotherapy Improves Survival in Advanced-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Insights from the IMpower133 Study

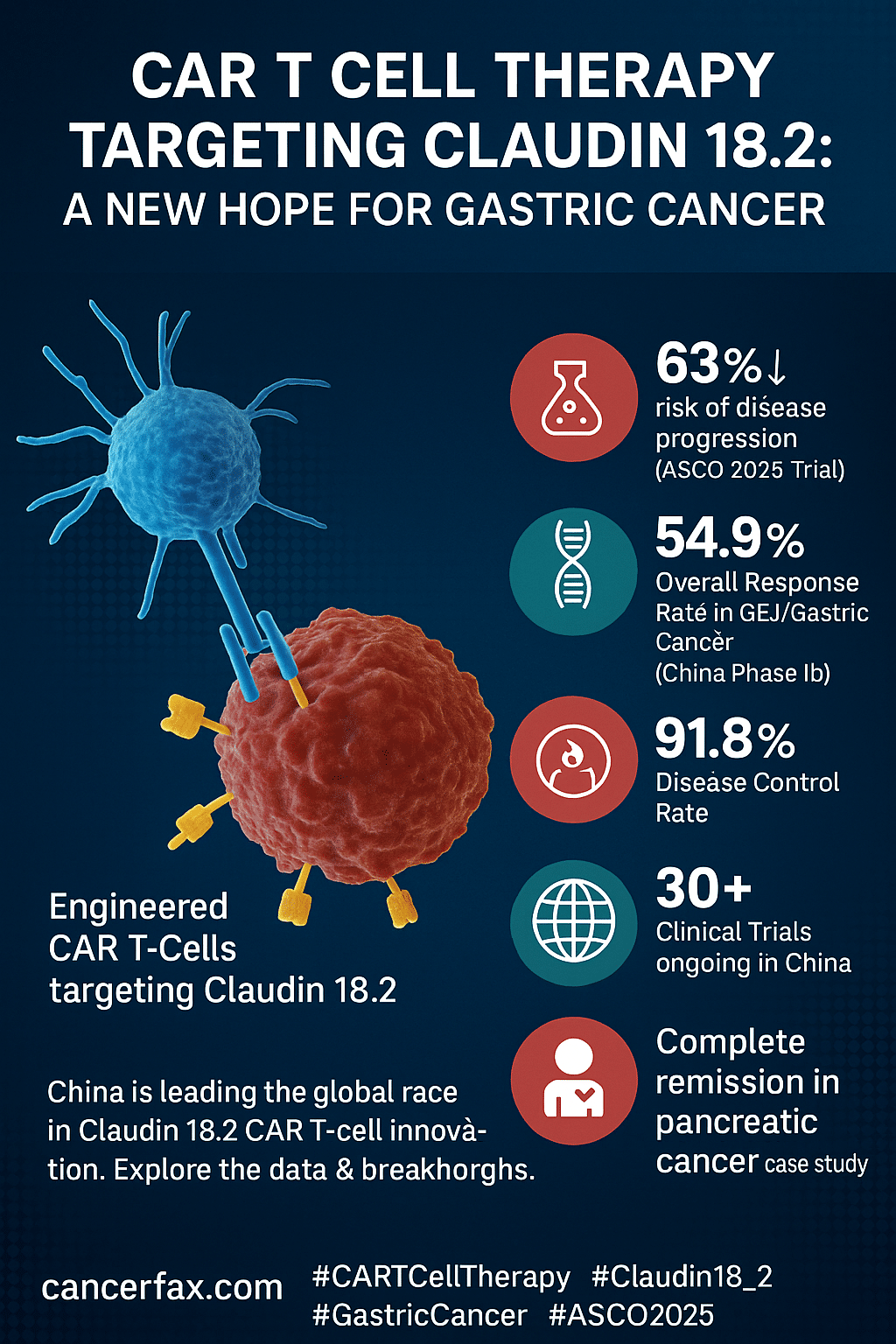

- Satri-cel CAR T-Cell Therapy: A New Era in Gastric Cancer Treatment

- AI & Technology (12)

- Aids cancer (4)

- Anal cancer (9)

- Appendix cancer (3)

- Basal cell carcinoma (1)

- Bile duct cancer (7)

- Biotech Innovations (19)

- Bladder cancer (12)

- Blood cancer (60)

- Bone cancer (12)

- Bone marrow transplant (47)

- Brain Cancer (1)

- Breakthrough Research (17)

- Breast Cancer (53)

- Cancer Guides (10)

- Cancer News and Updates (54)

- Cancer Treatment Abroad (286)

- Cancer treatment in China (316)

- Cancer Treatments (12)

- Cancer Types (5)

- Cancer Warriors (1)

- CAR T Protocols (2)

- CAR T-Cell therapy (135)

- Cervical cancer (40)

- Chemotherapy (55)

- Childhood cancer (2)

- Cholangiocarcinoma (3)

- Clinical trials (15)

- Colon cancer (96)

- Diagnosis & Staging (4)

- Doctors & Researchers (76)

- Drug Approvals (100)

- Drugs (80)

- Endometrial cancer (10)

- Esophageal cancer (15)

- Eye cancer (9)

- For Doctors and Researchers (12)

- Gall bladder cancer (3)

- Gastric cancer (29)

- Gene therapy (5)

- Glioblastoma (7)

- Glioma (10)

- Global Trial News (5)

- Gynecological cancer (2)

- Head and neck cancer (19)

- Hemato-Oncologist (1)

- Hematological Disorders (52)

- Hospital Reviews (3)

- How to Participate (6)

- Immunotherapy (34)

- Kidney cancer (10)

- Laryngeal cancer (1)

- Leukemia (49)

- Liver cancer (101)

- Lung cancer (82)

- Lymphoma (52)

- MDS (2)

- Melanoma (9)

- Merkel cell carcinoma (1)

- Mesothelioma (5)

- Myeloma (25)

- Myths vs Facts (5)

- Neuroblastoma (7)

- NK-Cell therapy (13)

- Nutrition (1)

- Ongoing Trials (11)

- Oral cancer (12)

- Ovarian Cancer (14)

- Pancreatic cancer (43)

- Paraganglioma (6)

- Patient Testimonials (1)

- Penile cancer (1)

- Prostrate cancer (11)

- Proton therapy (28)

- Radiotherapy (56)

- Recovery Tips (2)

- Rectal cancer (58)

- Research Insights (8)

- Sarcoma (14)

- Skin Cancer (13)

- Spine surgery (24)

- Stomach cancer (40)

- Success Stories (1)

- Surgery (102)

- Systemic mastocytosis (1)

- T Cell immunotherapy (7)

- Targeted therapy (9)

- Testicular cancer (5)

- Thoracic surgery (2)

- Throat cancer (6)

- Thyroid Cancer (15)

- Treatment Cost (1)

- Treatment in China (969)

- Treatment in India (1,273)

- Treatment in Israel (652)

- Treatment in Malaysia (425)

- Treatment in Singapore (321)

- Treatment in South Korea (305)

- Treatment in Thailand (291)

- Treatment in Turkey (272)

- Treatment Planning (151)

- Trial Results (2)

- Uncategorized (105)

- Urethral cancer (9)

- Urosurgery (14)

- Uterine cancer (4)

- Vaginal cancer (6)

- Vascular cancer (5)

- Vulvar cancer (1)

CancerFax is the most trusted online platform dedicated to connecting individuals facing advanced-stage cancer with groundbreaking cell therapies.

Send your medical reports and get a free analysis.

🌟 Join us in the fight against cancer! 🌟

Привет,

CancerFax — это самая надежная онлайн-платформа, призванная предоставить людям, столкнувшимся с раком на поздних стадиях, доступ к революционным клеточным методам лечения.

Отправьте свои медицинские заключения и получите бесплатный анализ.

🌟 Присоединяйтесь к нам в борьбе с раком! 🌟