Gastrointestinal stromal tumors

About Disease

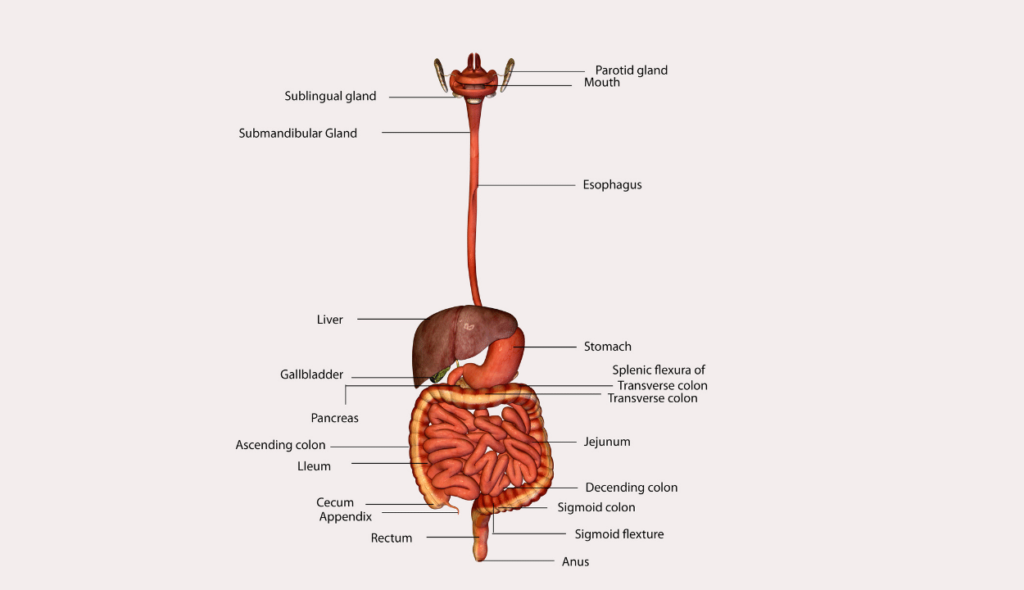

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) begin in very early stages in the interstitial cells of Cajal, a specific type of cell found in the GI tract wall (ICCs). ICCs are frequently referred to as the “pacemakers” of the digestive system because they tell the GI tract’s muscles to contract to move food and liquid along.

In the stomach, more than half of GISTs begin. GISTs can begin anywhere throughout the GI tract, unlike most other cancers, which often begin in the small intestine. A tiny percentage of GISTs begin outside the GI tract in surrounding regions such as the peritoneum or the omentum, which is a fatty layer that drapes over the abdominal organs like an apron (the thin lining over the organs and walls inside the abdomen).

Some GISTs seem much more likely than others to grow into other areas or spread to other parts of the body. Doctors look at certain factors to help tell whether a GIST is likely to grow and spread quickly, such as:

- The size of the tumor

- Where it’s located in the GI tract

- How fast the tumor cells are dividing.

Overview

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are uncommon mesenchymal neoplasms that arise from the interstitial cells of Cajal (ICCs) of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. They occur most frequently in the stomach (60%) and small intestine (30%), with fewer instances in the colon, rectum, and esophagus. GISTs are of varying degrees from benign to malignant, depending on tumor size, mitotic count, and site. The majority of GISTs are driven by mutations in the *KIT* or *PDGFRA* genes that cause uncontrollable cell growth.

Epidemiologically, GISTs are infrequent, with a predicted incidence of 10-15 cases per million worldwide each year. They are diagnosed mostly in adults between the ages of 50 and 70 years with no particular gender predisposition.

Even though the incidence is low, detection at an early stage has become possible with the advances in imaging modalities and increased awareness. GISTs can present with nonspecific signs such as abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding, or an abdominal mass but frequently can be asymptomatic until they enlarge considerably.

Improvements in molecular diagnosis and targeted therapy, especially tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g., imatinib), have greatly enhanced the outcome of patients with GISTs. Nonetheless, these patients must be followed up periodically to check for recurrence or drug resistance. Early diagnosis and molecular typing are still important for proper management.

Causes

The primary cause of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) is genetic mutations that lead to uncontrolled cell growth. Most GISTs arise due to mutations in specific genes that regulate cell signaling and proliferation. The two most common genetic mutations associated with GISTs are:

- KIT Gene Mutation:

Around 75-80% of GIST cases are caused by mutations in the KIT gene. The KIT gene encodes a receptor tyrosine kinase that regulates cell growth and survival. Mutations in this gene result in continuous activation of the receptor, promoting unregulated tumor growth. - PDGFRA Gene Mutation:

Approximately 10-15% of GISTs have mutations in the PDGFRA gene. This gene also encodes a tyrosine kinase receptor. Similar to KIT, mutations in PDGFRA lead to abnormal cell proliferation and tumor development. - SDH Deficiency:

In rare cases, GISTs may occur due to a deficiency in succinate dehydrogenase (SDH), a key enzyme in the mitochondrial energy cycle. SDH-deficient GISTs are often seen in younger patients and are linked to hereditary conditions like Carney-Stratakis syndrome. - Genetic Syndromes:

GISTs can also be associated with genetic syndromes such as Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) and Carney triad, increasing the risk of tumor development.

While environmental factors and lifestyle choices are not known to directly cause GISTs, understanding these genetic mutations plays a crucial role in diagnosis and targeted treatment.

Symptoms

The stomach or small intestine wall is where the majority of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) begin to grow. These tumors frequently expand into the GI tract’s free space, so unless they are in a specific area or reach a specific size, they might not immediately cause symptoms.

Small tumors may not show any symptoms and may be unintentionally discovered by the doctor when examining another issue. These little tumors frequently develop slowly.

Small GISTs may cause no symptoms, and they may grow so slowly that they don’t cause problems at first. As a GIST grows, it can cause signs and symptoms. They might include:

- Abdominal pain

- A growth you can feel in your abdomen

- Fatigue

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Cramping pain in the abdomen after eating

- Not feeling hungry when you would expect to

- Feeling full if you eat only a small amount of food

- Dark-colored stools caused by bleeding in the digestive system

GISTs can happen in people at any age, but they are most common in adults and very rare in children. The cause of most GISTs isn’t known. A small number are caused by genes passed from parents to children.

Symptoms due to blood loss

GISTs tend to be fragile tumors that can bleed easily. In fact, they are often found because they cause bleeding into the GI tract. Signs and symptoms of this bleeding depend on how fast it occurs and where the tumor is located.

- Brisk bleeding into the esophagus or stomach might cause the person to throw up blood. When the blood is thrown up, it may be partially digested, so it might look like coffee grounds.

- Brisk bleeding into the stomach or small intestine can make bowel movements (stools) black and tarry.

- Brisk bleeding into the large intestine is likely to turn the stool red with visible blood.

- If the bleeding is slow, it often doesn’t cause the person to throw up blood or have a change in their stool. Over time, though, slow bleeding can lead to a low red blood cell count (anemia), which can make a person feel tired and weak.

Bleeding from the GI tract can be grave. If you experience any of these signs or symptoms, please consult a doctor promptly.

Diagnosis

GISTs (gastrointestinal stromal tumors) are frequently discovered as a result of signs or symptoms. Other issues are discovered through exams or assessments. However, it’s not always possible to determine with absolute certainty if a person has a GIST or another sort of gastrointestinal (GI) tumor from these symptoms or preliminary tests. If a GI tumor is suspected, more testing will be required to identify it.

Medical history and physical examination

Your medical history, including your symptoms, potential risk factors, family history, and any medical disorders, will be discussed with the doctor.

To learn more about any physical symptoms of a GI tumor, such as an abdominal mass or other health issues, your doctor will perform a physical examination on you.

The doctor will perform imaging tests or endoscopy exams if there is a reason to believe you may have a GIST (or another type of GI tumor) to help determine whether it is cancer or something else. You can be referred to a specialist while seeing your primary care physician, such as a gastroenterologist (a doctor who treats diseases of the digestive system).

If a GIST is discovered, you will probably undergo additional testing to assist in identify the cancer’s stage (extent).

Imaging tests

Imaging tests use x-rays, magnetic fields, or radioactive substances to create pictures of the inside of the body. Imaging tests are done for several reasons, including:

- To help find out if a suspicious area might be cancer

- To learn how far cancer has spread

- To help determine if treatment has been effective

- To look for signs that the cancer has come back

Most people thought to have a GI tumor will get one or more of these tests.

Computed tomography (CT) scan

A CT scan creates finely detailed cross-sectional images of your body using x-rays. A CT scan produces precise images of the body’s soft tissues, unlike a standard x-ray.

Patients with (or at risk for) GISTs can benefit from CT scans to determine the size and location of a tumor as well as to determine whether it has migrated to other areas of the body.

In some circumstances, CT scans can also be utilized to accurately direct a biopsy needle into a potential cancerous area. These types of biopsies are often performed only if the results can influence the choice of treatment. However, this can be problematic if the tumor may be a GIST (because of the risk of bleeding and a probable increased risk of tumor spread).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan

MRI scans produce detailed pictures of the body’s soft tissues, just like CT scans do. However, MRI scans substitute radio waves and powerful magnets for x-rays.

Although CT scans are sufficient most of the time, MRI scans can occasionally be helpful in determining the extent of the cancer in the abdomen in individuals with GISTs. MRIs can also be used to check for cancer that has possibly returned (recurred) or spread (metastasized), especially in the brain or spine.

Barium X-Rays

Compared to earlier times, barium x-rays are no longer as frequently employed. They have been mostly supplanted by endoscopy and CT/MRI (where the doctor actually looks inside your esophagus, stomach, and intestines with a narrow fiberoptic scope – see below).

For these kinds of x-rays, the inner lining of the esophagus, stomach, and intestines is coated with a chalky liquid containing barium. This approach makes it simpler to see irregular lining sections on an x-ray. These exams are occasionally used to identify GI malignancies; however, they sometimes fail to detect small intestine tumors.

Most likely, you will need to begin fasting the evening before the test. You might need to take laxatives and enemas to clean out the bowels the night before or the morning of the exam if your colon is being inspected.

Barium swallow

When someone has a swallowing issue, this is frequently the initial test that is performed. You consume a barium-containing beverage to coat the lining of your esophagus in preparation for this test. The following few minutes are spent taking a series of x-rays.

Upper GI series

With the exception of the fact that x-rays are taken after the barium has had time to cover the stomach and the first portion of the small intestine, this test is comparable to the barium swallow. More x-rays can be taken during the following few hours as the barium travels through to check for issues in the remaining small intestine. An example of this is a little bowel follow-through.

Enteroclysis

Your mouth or nose, esophagus, stomach, and beginning of the small intestine are all entered through a tiny tube. A substance that increases the amount of air in the intestines and causes them to expand is also delivered through the tube with the barium. The intestines are then radiographed after that. Compared to a small bowel follow-through, this test can provide better views of the small intestine but is also more painful.

Barium enema

This test, sometimes referred to as a lower GI series, examines the large intestine’s inner surface (colon and rectum). While you are reclining on the x-ray table, a short, flexible tube is put in the anus to provide the barium solution for this test. To help move the barium toward the colon wall and better cover the inner surface, air is frequently pumped in through the tube as well. An air-contrast barium enema or double-contrast barium enema is what this is. To help disseminate the barium and to gain multiple perspectives of the colon, you could be requested to adjust your position. Thereafter, x-rays are taken in one or more sets.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan

You receive an injection containing a mildly radioactive sugar that concentrates mostly in cancer cells to have a PET scan. Then, a photograph of the body’s radioactive regions is made using a specific camera. While a PET scan cannot provide the same level of information as a CT or MRI scan, it may simultaneously screen for potential cancer spread throughout the entire body.

Nowadays, many facilities have equipment that can do a PET and CT scan simultaneously (PET/CT scan). This type of imaging enables the clinician to have a closer look at any regions that “lit up” on the PET scan.

When CT or MRI scan results are unclear, PET scans can be helpful for examining GISTs. This examination can also be done to search for potential sites where the cancer may have metastasized to assess whether surgery is an option.

The effectiveness of a pharmacological treatment can also be determined using PET scans, which frequently provide results more quickly than CT or MRI scans. The scan is often performed a few weeks after the medicine is first taken. The tumor will quit absorbing the radioactive sugar if the medication is functioning. Your doctor might decide to alter your medicine therapy if the tumor continues to absorb the sugar.

Endoscopy

A flexible, illuminated tube with a tiny video camera on the end is called an endoscope, and it is inserted into the body during an endoscopy to view the GI tract’s inner lining. Small bits can be biopsied (removed) through the endoscope if abnormal areas are discovered. To determine whether the biopsy samples have cancer and, if so, what form of cancer, they will be examined under a microscope.

GISTs are frequently seen below the mucosa, or outer layer, of the GI tract’s inner lining. Unlike more frequent GI tract tumors, which often begin in the mucosa, they may be more difficult to see with endoscopy. If a GIST is present, the doctor might only be able to observe a bulge under the generally smooth surface. Additionally, GISTs underneath the mucosa are more difficult to biopsy with an endoscope. This phenomenon is one of the main causes of undiagnosed GISTs prior to surgery.

There is a higher likelihood that the GIST will spread to other parts of the body if the tumor has penetrated the GI tract’s inner lining and is visible on endoscopy.

Upper endoscopy

In this operation, the inner lining of the esophagus, stomach, and first segment of the small intestine are examined using an endoscope that is introduced through the mouth and down the neck. Any aberrant sites may be the subject of biopsy samples.

A hospital, an outpatient surgery center, or a doctor’s office can all do an upper endoscopy. Usually, you receive medication via an intravenous (IV) line to induce sleep prior to the exam. The examination itself typically takes between 10 and 20 minutes, but if a tumor is discovered or biopsy samples need to be collected, the time may increase.

Colonoscopy

A colonoscope, a specific kind of endoscope, is introduced via the anus and up into the colon during a colonoscopy. This enables the physician to examine the colon’s and rectum’s inner lining and collect biopsy samples from any abnormal spots.

It must be thoroughly cleaned before the test to gain a clear view of the colon’s interior. You’ll receive detailed instructions from your doctor. Before the test, you might need to adhere to a particular diet for a day or more. Additionally, you might need to consume a significant amount of a liquid laxative the night before, which will require you to spend a lot of time in the restroom.

An outpatient surgery center, a doctor’s office, or a hospital are all possible places to have a colonoscopy done. Most likely, an intravenous (IV) medication will be administered to you before the treatment to help you feel at ease and asleep. Less frequently, general anesthesia may be administered to put you into a profound slumber. The examination normally lasts 15 to 30 minutes, but if a tumor is discovered or a sample is required, the time may be extended.

Capsule endoscopy

Both colonoscopy and upper endoscopy are unable to access the entire small intestine. One method of viewing the small intestine is with a capsule endoscope.

An endoscope is not actually used in this process. Instead, a light source and a tiny camera are included in a capsule that you ingest. This capsule is about the size of a large vitamin tablet. The capsule passes through the stomach and into the small intestine like any other pill would.

It captures thousands of images while it passes through the intestine, which typically takes around 8 hours. These photos are electronically transferred to a waist-worn device. The doctor can examine the images as a video after downloading them onto a computer. During a typical bowel movement, the capsule leaves the body and is eliminated.

You can carry on with your regular daily activities while the capsule passes through the GI tract since this test doesn’t require sedation. The most effective applications for this relatively new method are still being researched. One drawback is that throughout the test, any aberrant regions that are visible cannot be biopsied.

Double balloon enteroscopy (endoscopy)

This is an alternative perspective on the small intestine. Regular endoscopy cannot provide a thorough examination of the small intestine due to its length and complexity. However, this technique avoids them by utilizing a unique endoscope that consists of 2 tubes, one inside the other.

You receive general anesthetic or intravenous (IV) medication to help you relax (so that you are asleep). Depending on whatever section of the small intestine needs to be inspected, the endoscope is subsequently entered either through the mouth or the anus.

The camera-equipped inner tube is advanced roughly a foot ahead once it is within the small intestine as the doctor examines the lining. The endoscope is then anchored by inflating a balloon on its tip. A second balloon is used to secure the outer tube in place when it is advanced to almost reach the end of the inner tube.

The endoscope is again advanced after the first balloon has been inflated. The doctor can visualize the intestine one foot at a time by repeatedly performing this procedure. It can take hours to finish the test.

Along with capsule endoscopy, this test can be performed. The primary benefit of this test over capsule endoscopy is the ability for the physician to do a biopsy if an abnormality is discovered. Because you are given medication to keep you drowsy for the procedure, similar to other forms of endoscopy.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)

This kind of imaging examination makes use of an endoscope. Sound waves are used in ultrasound to take photographs of the body’s organs. A transducer—a wand-like probe—is applied to the skin during the majority of ultrasonic exams. The probe emits sound waves, which are then picked up by a pattern of echoes.

The ultrasonic probe for an EUS is located at the endoscope’s tip. This enables the probe to be positioned very next to (or on top of) a GI tract tumor. The probe emits sound waves and then listens for the echoes that return, much like a conventional ultrasound. The echoes are then converted by a computer into a picture of the area being examined.

The specific position and size of the GIST can be discovered using EUS. It is helpful in determining how far a tumor has encroached on the GI tract wall (or beyond it and into a nearby organ). If the tumor has migrated to neighboring lymph nodes, the test can also assist in identify those nodes. A needle biopsy can also be guided with its assistance (see below). Before this treatment, you will normally get medication to put you to sleep.

Biopsy

Even if an abnormality is seen on an imaging test, such as a CT scan or barium x-ray, these procedures frequently cannot determine with certainty whether the abnormality is a GIST, another sort of tumor (benign or cancerous), or some other ailment (like an infection).

Removing cells from the area is the only way to be certain of what it is. This process is known as a biopsy. The cells are then transported to a lab, where a pathologist examines them under a microscope and may do additional tests on them.

Not all patients with tumors that could be GISTs require a biopsy prior to treatment. A biopsy is often only performed if it will aid in determining treatment choices if a doctor suspects a tumor is a GIST. GISTs are frequently weak tumors that are prone to disintegrating and bleeding quickly. Any biopsy must be performed with extreme caution due to the possibility that it could result in bleeding or perhaps raise the danger of cancer spreading.

Endoscopic biopsy

An endoscope can be used to collect biopsy samples. In order to obtain a small sample of the tumour when one is discovered, the doctor can pass biopsy forceps (pincers or tongs) through the tube.

Despite the tiny sample size, doctors may frequently provide a reliable diagnosis. However, with GISTs, the tumor may occasionally be hidden beneath the inner lining of the stomach or intestine, preventing the biopsy forceps from penetrating deep enough to reach it.

Although it is uncommon, bleeding from a GIST following a biopsy can be a major issue. If this happens, medical professionals may use an endoscope to inject medications into the tumor to shrink blood vessels and stop the bleeding.

Needle biopsy

A small sample of the area can also be taken using a thin, hollow needle during a biopsy. When performing an endoscopic ultrasound is the most typical approach to achieve this (described above). A needle on the endoscope’s tip is guided into the tumor by the physician using an ultrasound image as a guide. An endoscopic ultrasound-guided tiny needle aspiration is what this is (EUS-FNA).

Less frequently, the doctor might use an imaging test like a CT scan to guide the placement of a needle through the skin and into the tumor. Percutaneous biopsy is the term used for this.

Surgical biopsy

The doctor can advise waiting until surgery to remove the tumor to collect a sample if an endoscopic or needle biopsy is not possible or if the outcome of a biopsy would not impact treatment options.

The procedure is known as a laparotomy if a significant abdominal incision is used to perform the surgery. Occasionally, the tumor can be sampled (or small tumors can be excised) using a laparoscope, a thin, illuminated tube that allows the surgeon to see within the abdomen through a little incision.

The surgeon can sample (or remove) the tumor using long, thin surgical instruments inserted through additional small abdominal incisions. Laparoscopic or keyhole surgery is the term used for this.

Lab tests

Once tumor samples are obtained, a pathologist might be able to tell that a tumor is most likely a GIST just by looking at the cells with a microscope. But sometimes further lab tests might be needed to be certain.

Immunohistochemistry: For this test, a part of the sample is treated with man-made antibodies that will attach only to a certain protein in the cells. The antibodies cause color changes if the protein is present, which can be seen under a microscope.

If GIST is suspected, some of the proteins most often tested for are KIT (also known as CD117) and DOG1. Most GIST cells have these proteins, but cells of most other types of cancer do not, so tests for these proteins can help tell whether a GI tumor is a GIST or not. Other proteins, such as CD34, might be tested for as well.

Molecular genetic testing: Testing might also be done to look for mutations in the KIT or PDGFRA genes, as most GIST cells have mutations in one or the other. Testing for mutations in these genes can also help determine if certain targeted therapy drugs are likely to be helpful in treating the cancer.

Less often, tests might be done to search for changes in other genes, such as the SDH genes.

Mitotic rate: If a GIST is diagnosed, the doctor will also look at the cancer cells in the sample to see how many of them are actively dividing into new cells. This quantity is known as the mitotic rate (or mitotic index). A low mitotic rate means the cancer cells are growing and dividing slowly, while a high rate means they are growing quickly. The mitotic rate is an important part of determining the stage of the cancer.

Blood tests

Your doctor may order some blood tests if they think you may have a GIST. There are no blood tests that can tell for sure if a person has a GIST. But blood tests can sometimes point to a possible tumor (or to its spread). For example:

- A complete blood count (CBC) can show if you have a low red blood cell count (that is, if you are anemic). Some people with GISTs may become anemic because of bleeding from the tumor.

- Abnormal liver function tests may mean that the GIST has spread to your liver.

Blood tests are also done to check your overall health before surgery or while you get other treatments, such as targeted therapy.

Treatment and Management

Surgery for GIST

When a tumor is small, it is frequently possible to remove it together with a small patch of healthy tissue surrounding it. This is accomplished by making an incision in the skin. Since GISTs nearly never migrate to the lymph nodes, unlike many other malignancies, there is typically no need to remove the lymph nodes in the area.

“Keyhole” (laparoscopic) surgery is an option for some tiny malignancies. To remove the tumor, multiple small incisions are performed rather than one large one. The surgeon inserts a laparoscope, a narrow, illuminated tube with a tiny video camera on the end, through one of the incisions. This step enables them to view the abdomen. The tumor is then removed using long, thin surgical instruments through the other wounds. Patients typically recover more quickly from this sort of surgery than from conventional surgery, which requires a larger incision, because the incisions are smaller.

Surgery for larger GIST’s

The surgeon could still be able to completely remove the tumor even if it is huge or spreading to other organs. It could be necessary to remove a portion of the intestines or other organs to do this. Additionally, the surgeon may remove malignancies that have migrated to the liver or other organs in the abdomen.

Taking the targeted medication imatinib (Gleevec) initially, often for at least a few months, may be another option for cancers that are big or have spread into neighboring areas. Neoadjuvant therapy, as it is known, frequently causes the tumor to shrink, making surgery to remove it easier.

Surgery for metastatic GISTs

For a GIST that has expanded (metastasized) to other areas of the body, surgery is not a usual treatment. The initial line of treatment for metastatic GISTs is typically targeted therapy medications. However, some medical professionals could suggest surgery to remove the metastatic tumors if there are only a few of them and they react well to targeted therapy. Although no sizable research has been conducted to demonstrate how useful such surgery is, it may be a choice. Make sure you understand the purpose of the procedure and any possible side effects if your doctor recommends it.

Other alternatives could include various local treatments like embolization or ablation if the liver-based malignancies are difficult to remove.

Ablation and embolization to treat gastrointestinal stromal tumors

Treatments like ablation and embolization may be utilized if a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) has progressed to the liver, especially if surgery is unable to eliminate the tumors.

Ablation

Ablation is the term for the removal of tumors through the use of chemicals, high temperatures, or both. It can occasionally be utilized to eliminate GISTs that have only developed a few little tumors in the liver. Ablation might not be the best option for treating tumors close to critical structures like major blood arteries, the diaphragm (the thin breathing muscle above the liver), or major ducts in the liver because it frequently destroys some of the normal tissue surrounding the tumor.

There are several types of ablation:

- Radiofrequency ablation (RFA), which uses high-energy radio waves to heat the tumor and destroy cancer cells

- Ethanol (alcohol) ablation, where concentrated alcohol is injected directly into the tumor to kill cancer cells

- Microwave thermotherapy, where microwaves transmitted through a probe placed in the tumor are used to heat and destroy the cancer cells

- Cryosurgery (cryotherapy), which destroys a tumor by freezing it using a thin metal probe,. This method sometimes requires general anesthesia (you are in deep sleep and not able to feel pain)

Embolization

Embolization is a treatment in which the doctor administers medications to stop or lessen the blood flow to cancerous liver cells.

Given that it contains two blood supplies, the liver is uncommon. Branches of the portal vein feed the majority of normal liver cells, whereas branches of the hepatic artery often feed the majority of cancerous liver cells. The majority of healthy liver cells are not damaged because they receive their blood supply through the portal vein; however, blocking the branch of the hepatic artery feeding the tumor does aid in the death of the cancer cells.

Embolization does restrict part of the blood flow to the healthy liver tissue; thus, it may not be a suitable option for some individuals whose livers have already suffered liver damage from conditions like cirrhosis or hepatitis.

Targeted therapy for GIST

Certain proteins that aid in cell division and growth in gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) cells can be targeted by some medications. When treating GISTs, these focused medications—also known as precision medications—are frequently highly beneficial. They function differently than conventional chemotherapy (chemo) medications, which are typically ineffective.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are the name given to the targeted medications used to treat GISTs because they specifically target proteins known as KIT and PDGFRA, which are tyrosine kinases.

These targeted medications are all given orally, often once per day.

Targeted therapy drugs used for treatment of GISTs:

- Imatinib

- Sunitinib

- Regorafenib

- Ripretinib

- Avapritinib

- Sorafenib (Nexavar)

- Nilotinib (Tasigna)

- Dasatinib (Sprycel)

- Pazopanib (Votrient)

Chemotherapy

Drugs are used in chemotherapy, also known as “chemo,” to treat cancer. These medications are frequently administered intravenously (IV) or orally. This medication may be helpful for malignancies that have spread past the organ they originated in because they enter the bloodstream and circulate throughout the body.

Chemotherapy refers to the use of any drug to treat cancer, including targeted therapy medications like imatinib (Gleevec), which are now frequently used to treat gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs). However, the term “chemo” is typically used to refer to specific medications that target rapidly proliferating cells anywhere in the body, including cancer cells.

Radiation therapy for GIST’s treatment

High-energy x-rays (or other particles) are used in radiation treatment to kill cancer cells. Radiation is not frequently utilized since it is not particularly effective in treating gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs). However, it can occasionally be used to treat symptoms like bone discomfort.

The radiation experts will take precise measurements before the start of your treatment to determine the right angles for aiming the radiation beams and the right amount of radiation. Imaging tests like CT or MRI scans are frequently performed as part of this planning session, known as simulation.

Similar to receiving an x-ray, radiation therapy uses greater radiation. The actual procedure is painless. Even though the setup process getting you situated for treatment—usually takes longer, it only takes a few minutes. Radiation therapy may go on for several days straight.

Prevention

Currently, there are no guaranteed methods to prevent gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) because most cases arise from spontaneous genetic mutations rather than modifiable risk factors. Unlike many other cancers, GISTs are not strongly linked to lifestyle choices, environmental factors, or specific behaviors.

However, certain approaches may help in early detection and management, especially for individuals with a higher genetic predisposition:

- Genetic Counseling and Testing:

Individuals with a family history of GISTs or genetic syndromes like Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) or Carney-Stratakis syndrome may benefit from genetic counseling and testing. Early genetic screening can help in monitoring and detecting tumors at an early stage. - Regular Medical Check-ups:

Those with a known genetic predisposition or a history of gastrointestinal disorders should undergo regular imaging tests like endoscopy, CT scans, or MRI. Early diagnosis allows for timely intervention. - Managing Risk Factors:

Although no direct lifestyle risk factors are identified, maintaining a healthy lifestyle through a balanced diet, regular exercise, and avoiding smoking and excessive alcohol consumption may contribute to overall well-being and reduce the risk of other cancers. - Monitoring for Secondary Cancers:

Patients with hereditary conditions associated with GISTs should remain vigilant for other cancers that may co-occur and follow their healthcare provider’s screening recommendations.

While prevention may not be entirely possible, awareness and early detection can significantly improve treatment outcomes.

Prognosis

The prognosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) varies significantly depending on several factors, including the tumor size, location, mitotic index (rate of cell division), genetic mutations, and whether the cancer has metastasized.

- Localized GISTs:

Patients diagnosed with localized, non-metastatic GISTs generally have a favorable prognosis. Surgical removal of the tumor is often curative, especially if it is detected early. The 5-year survival rate for localized GISTs can exceed 90%. - High-Risk or Aggressive GISTs:

Larger tumors (greater than 5 cm) or those with a high mitotic rate pose a greater risk of recurrence and metastasis. For these cases, targeted therapies like imatinib (a tyrosine kinase inhibitor) are often recommended post-surgery to reduce the likelihood of recurrence. - Metastatic or Inoperable GISTs:

For patients with metastatic disease, the prognosis is less favorable. However, advancements in targeted therapy have significantly improved survival. Many patients can manage the disease for years with drugs like imatinib, sunitinib, or regorafenib. The median survival for metastatic GIST patients receiving appropriate treatment is approximately 5 years or longer. - SDH-Deficient and PDGFRA-Mutant GISTs:

Specific genetic mutations can influence prognosis. PDGFRA mutations often respond well to targeted therapies, whereas SDH-deficient GISTs may be more challenging to treat. - Monitoring and Follow-up:

Regular follow-ups with imaging are essential to monitor for recurrence. With advancements in precision medicine and ongoing clinical trials, the outlook for GIST patients continues to improve.

Early detection, molecular testing, and appropriate therapy play a crucial role in ensuring better survival outcomes and improved quality of life.

Living with Disease

Living with gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) can be challenging, but with the right medical care, support, and lifestyle adjustments, many patients can maintain a good quality of life. Management often involves ongoing treatment, regular monitoring, and coping with both physical and emotional challenges.

- Managing Treatment Side Effects:

Many GIST patients undergo targeted therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) like imatinib. While effective, these medications may cause side effects such as fatigue, nausea, muscle cramps, and skin rashes. Open communication with healthcare providers ensures timely management of side effects through supportive therapies. - Regular Monitoring and Follow-ups:

After initial treatment, patients require routine imaging tests (CT scans or MRIs) to monitor for recurrence. Maintaining follow-up appointments and adhering to the recommended surveillance plan is essential. - Nutritional Support:

Some GIST patients may experience digestive issues, particularly after surgery or if tumors affect the stomach or intestines. A balanced diet, often recommended by a dietitian, can help manage symptoms like nausea or poor appetite. Small, frequent meals and hydration are commonly advised. - Emotional and Psychological Support:

A cancer diagnosis can trigger anxiety, depression, and emotional distress. Seeking support from mental health professionals, counselors, or support groups can provide emotional resilience. Many organizations offer resources tailored for GIST patients. - Staying Physically Active:

Moderate exercise, like walking or yoga, can help improve energy levels, reduce stress, and maintain overall health. However, patients should consult their doctors before starting any exercise program. - Building a Support Network:

Family, friends, and caregivers play a crucial role in supporting patients emotionally and practically. Joining patient advocacy groups or connecting with other GIST survivors can also provide comfort and valuable insights.

With advancements in targeted therapy and improved monitoring techniques, many patients can live active and fulfilling lives despite a GIST diagnosis.

Lifestyle and Nutrition

Maintaining a healthy lifestyle and balanced nutrition is crucial for individuals living with gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs). While no specific diet can cure GISTs, appropriate dietary choices and lifestyle habits can help manage symptoms, support overall health, and improve quality of life.

1. Nutrition for GIST Patients

- Focus on Balanced Nutrition: A diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins can provide essential nutrients and strengthen the immune system.

- Small, Frequent Meals: Patients who experience digestive discomfort or have undergone surgery may benefit from eating smaller meals more frequently to avoid bloating or indigestion.

- Hydration: Drinking plenty of water is essential, especially for those experiencing nausea or diarrhea due to medications like tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs).

- Low-Fat, High-Fiber Diet: Fiber-rich foods like vegetables, legumes, and whole grains can aid digestion. However, those prone to bloating or obstruction may need to adjust fiber intake under medical guidance.

- Limit Processed Foods: Reducing consumption of ultra-processed foods, red meat, and high-sugar products can support general well-being.

- Manage Side Effects: If nausea or loss of appetite occurs, bland foods, ginger tea, or small snacks may help. In cases of mouth sores from treatment, soft, cool foods can offer relief.

2. Lifestyle Recommendations

- Regular Physical Activity: Light exercises like walking, yoga, or swimming can reduce fatigue, improve mood, and enhance overall well-being. Consult a doctor before starting any exercise regimen.

- Weight Management: Maintaining a healthy weight reduces the risk of complications and supports overall recovery.

- Stress Management: Mindfulness, meditation, counseling, or joining a support group can help manage stress and anxiety.

- Avoid Alcohol and Tobacco: Both alcohol and smoking may interfere with medications and overall treatment effectiveness.

- Routine Medical Check-ups: Regular follow-ups ensure timely management of any side effects or disease progression.

By adopting a balanced diet and maintaining a physically active and positive lifestyle, GIST patients can enhance their quality of life and improve treatment outcomes.

Research and Advancements

Significant advancements in the understanding and treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) have improved patient outcomes over the past two decades. Ongoing research continues to explore novel therapies, refine existing treatments, and identify biomarkers for better diagnosis and management.

1. Targeted Therapy Advancements

- Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (TKIs):

Imatinib (Gleevec) revolutionized GIST treatment as the first approved TKI targeting mutated KIT and PDGFRA genes. Subsequent TKIs like Sunitinib (Sutent) and Regorafenib (Stivarga) have provided effective options for patients with imatinib-resistant tumors. - Next-Generation TKIs:

Drugs like Ripretinib (Qinlock) and Avapritinib (Ayvakit) are approved for advanced or resistant GISTs. These agents target additional mutations, offering improved control for patients with difficult-to-treat tumors.

2. Molecular and Genetic Research

- Researchers are exploring novel gene mutations beyond KIT and PDGFRA, including SDH-deficient GISTs and rare mutations that respond to emerging therapies.

- Liquid biopsies using circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) are under investigation for non-invasive monitoring of mutations and treatment resistance.

3. Immunotherapy and Combination Approaches

- Immunotherapy using immune checkpoint inhibitors is being evaluated for GIST patients, particularly those with high tumor mutation burden or resistance to TKIs.

- Combining TKIs with other agents like MEK inhibitors or PI3K inhibitors is also being explored to overcome drug resistance.

4. Personalized Medicine

- Advances in genetic profiling allow personalized treatment plans based on individual tumor mutations. Tailoring therapies according to specific genetic alterations has shown improved response rates.

5. Clinical Trials and Emerging Therapies

- Ongoing clinical trials are testing novel therapies targeting secondary resistance mutations and exploring combination treatments. Patients with rare or resistant GIST subtypes are encouraged to participate in these trials.

Through continuous research and advancements, the prognosis for GIST patients has significantly improved, with targeted therapies offering long-term disease management and extended survival.

Support and Resources

Living with a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) can be challenging, but numerous support systems and resources are available to help patients, caregivers, and families navigate the diagnosis, treatment, and recovery process. Accessing these resources can provide emotional, financial, and medical assistance.

1. Patient Support Groups and Organizations

- The Life Raft Group (LRG): A global patient advocacy organization offering support, educational resources, clinical trial information, and opportunities to connect with other GIST patients.

- GIST Support International (GSI): Provides comprehensive information about GIST diagnosis, treatment, and management. It also offers an online forum for patients and caregivers.

- CancerCare: Offers free counseling, support groups, and financial assistance to cancer patients, including those with GIST.

2. Medical and Clinical Resources

- National Cancer Institute (NCI): Provides up-to-date information on GIST research, clinical trials, and treatment guidelines.

- American Cancer Society (ACS): Offers resources on understanding GIST, finding treatment centers, and accessing supportive care services.

- ClinicalTrials.gov: A valuable resource for finding ongoing clinical trials for GIST patients, particularly for those with drug-resistant or recurrent tumors.

3. Financial Assistance Programs

- Pharmaceutical companies often provide patient assistance programs to help with the cost of targeted therapies like imatinib, sunitinib, and regorafenib.

- Nonprofit organizations and foundations may offer financial aid for travel, lodging, and treatment expenses.

4. Emotional and Psychological Support

- Counseling Services: Oncology social workers and mental health professionals can help manage the emotional challenges of living with GIST.

- Peer Support Groups: Many patients find comfort in connecting with others who have experienced similar journeys through in-person or virtual support groups.

5. Caregiver Support

- Caregivers can access resources tailored to their needs, including respite care, counseling, and educational materials through organizations like the Cancer Support Community and Family Caregiver Alliance.

Accessing these resources ensures that GIST patients receive comprehensive support throughout their cancer journey, improving both physical and emotional well-being.

Clinical Trials

Clinical trials play a pivotal role in advancing the treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), providing access to cutting-edge therapies and novel drug combinations. For patients who have exhausted standard treatments or developed resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), participation in clinical trials can offer new hope.

1. Importance of Clinical Trials for GISTs

- Clinical trials evaluate the safety and effectiveness of emerging therapies, including next-generation TKIs, immunotherapy, and combination therapies.

- Trials are essential for patients with rare mutations such as PDGFRA D842V or SDH-deficient GISTs, for which treatment options are limited.

- They also study strategies to overcome resistance in metastatic or recurrent GIST cases.

2. Ongoing GIST Clinical Trials in China

China has emerged as a significant center for GIST clinical trials due to its advanced oncology research infrastructure and large patient population. Several hospitals and research institutions conduct trials in collaboration with global pharmaceutical companies. Key areas of focus include:

- Next-Generation TKIs: Drugs like Avapritinib and Ripretinib have been extensively tested in Chinese trials, particularly targeting resistant GISTs.

- Combination Therapies: Studies combining TKIs with immunotherapy or chemotherapy are evaluating their effectiveness in enhancing treatment response.

- Targeted Therapy for Rare Mutations: Trials in China also explore novel agents for SDH-deficient GISTs and KIT exon mutations.

- Precision Medicine Approaches: Some trials use molecular profiling to customize therapies based on a patient’s genetic mutations.

3. Major Clinical Trial Centers in China

- Peking University Cancer Hospital and Fudan University Cancer Hospital are leading sites for GIST trials.

- Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center is renowned for conducting trials focused on drug resistance mechanisms.

- Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences collaborates internationally on breakthrough therapies.

4. How to Access Clinical Trials

Patients interested in participating in GIST clinical trials in China can:

- Consult with their oncologist to identify suitable trials.

- Visit platforms like ClinicalTrials.gov or China Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR) for up-to-date information.

- Reach out to cancer support organizations like CancerFax for assistance in navigating trial options.

Clinical trials offer GIST patients access to the latest treatment innovations, contributing to the global advancement of cancer care.

Healthcare and Insurance

Managing gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) often involves a combination of specialized medical care, advanced treatments, and long-term follow-ups. Understanding healthcare options and navigating insurance coverage is essential for ensuring timely and effective treatment.

1. Healthcare for GIST Patients

- Specialized Cancer Centers: Patients with GISTs should seek care at cancer hospitals or centers experienced in treating rare tumors. Multidisciplinary teams, including oncologists, surgeons, and genetic counselors, provide comprehensive care.

- Targeted Therapy Access: Access to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) like imatinib, sunitinib, and ripretinib is crucial. Leading oncology hospitals often offer the latest therapies and access to clinical trials.

- International Medical Travel: In regions where specialized treatment is unavailable, patients may consider medical tourism to countries like China, which offers advanced GIST therapies and clinical trial opportunities. Organizations like CancerFax facilitate medical travel arrangements.

2. Health Insurance Coverage

- Private Health Insurance: Many private insurers cover GIST treatments, including surgeries, medications, and hospital stays. Patients should confirm whether targeted therapies and clinical trials are included in their plans.

- Government Programs: In countries with public healthcare systems, government-funded programs often provide financial assistance for cancer treatment. For example, China’s National Healthcare Security Administration (NHSA) offers partial reimbursement for some GIST medications.

- International Health Insurance: Patients traveling abroad for treatment should ensure their international health insurance covers cancer care, hospitalization, and emergency services.

- Clinical Trial Coverage: Some trials cover treatment costs for participants, including medications and regular monitoring. Patients should discuss financial aspects with trial coordinators before enrollment.

3. Financial Assistance Programs

- Pharmaceutical companies often provide Patient Assistance Programs (PAPs) to reduce the cost of expensive TKIs for eligible patients.

- Nonprofit organizations and cancer foundations may offer financial support for uninsured or underinsured patients.

4. Navigating Insurance Claims

- Patients are advised to keep detailed medical records and consult with a hospital’s financial counselor or patient advocate for insurance guidance.

- Understanding policy terms, including coverage limits and exclusions, can prevent unexpected expenses.

By exploring all available healthcare and insurance options, GIST patients can access life-saving treatments and manage the financial burden of cancer care.