Hot and cold pancreatic cancer tumors

A research team from the Abramson Cancer Center (ACC) at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine found that whether a tumor is hot or cold is determined by information embedded in the cancer cells themselves. “Hot” tumors are often considered more sensitive to immunotherapy. In a new study published this week in Immunity, the researchers explored the role of “tumor heterogeneity”, namely the ability of tumor cells to move, replicate, metastasize and respond to treatment. These new findings can help oncologists more accurately tailor the unique tumor composition of patients.

Ben Stanger, a professor of gastroenterology and cell and developmental biology at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, said that the degree to which T cells are attracted to tumors is regulated by the tumor-specific genes. In order for tumors to grow, they need to avoid attacks by the immune system. There are two ways: to develop into cold tumors, or hot tumors that can deplete T cells, effectively protecting tumor cells from damage to the patient’s immune system.

In this study, researchers found that whether a tumor is hot or cold determines whether it will respond to immunotherapy. Cold tumor cells produce a compound called CXCL1, which can instruct bone marrow cells to enter the tumor, keep T cells away from the tumor, and ultimately make the immunotherapy insensitive. In contrast, knocking out CXCL1 in cold tumors promotes T cell infiltration and sensitivity to immunotherapy.

The team generated a series of cell lines that mimic the characteristics of pancreatic tumors, including the types of immune cells they contain. In the future, these tumor cell lines can help further identify and optimize treatment for specific subtypes of patients with various tumor heterogeneity states.

- Alysha Mendossahttps://cancerfax.com/author/alysha/

- Alysha Mendossahttps://cancerfax.com/author/alysha/

- Alysha Mendossahttps://cancerfax.com/author/alysha/

- Alysha Mendossahttps://cancerfax.com/author/alysha/

Related Posts

- Comments Closed

- April 20th, 2020

- Datopotamab deruxtecan-dlnk is approved by the USFDA for EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer

- Tafasitamab-cxix is approved by the USFDA for relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma

- PiggyBac Transposon System: A Revolutionary Tool in Cancer Gene Therapy

- Breakthrough Treatments for Advanced Breast Cancer in 2025

- Neoadjuvant and adjuvant pembrolizumab is approved by the USFDA for resectable locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- Mitomycin intravesical solution is approved by the USFDA for recurrent low-grade intermediate-risk non-muscle invasive bladder cancer

- Taletrectinib is approved by the USFDA for ROS1-positive non-small cell lung cancer

- Darolutamide is approved by the USFDA for metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer

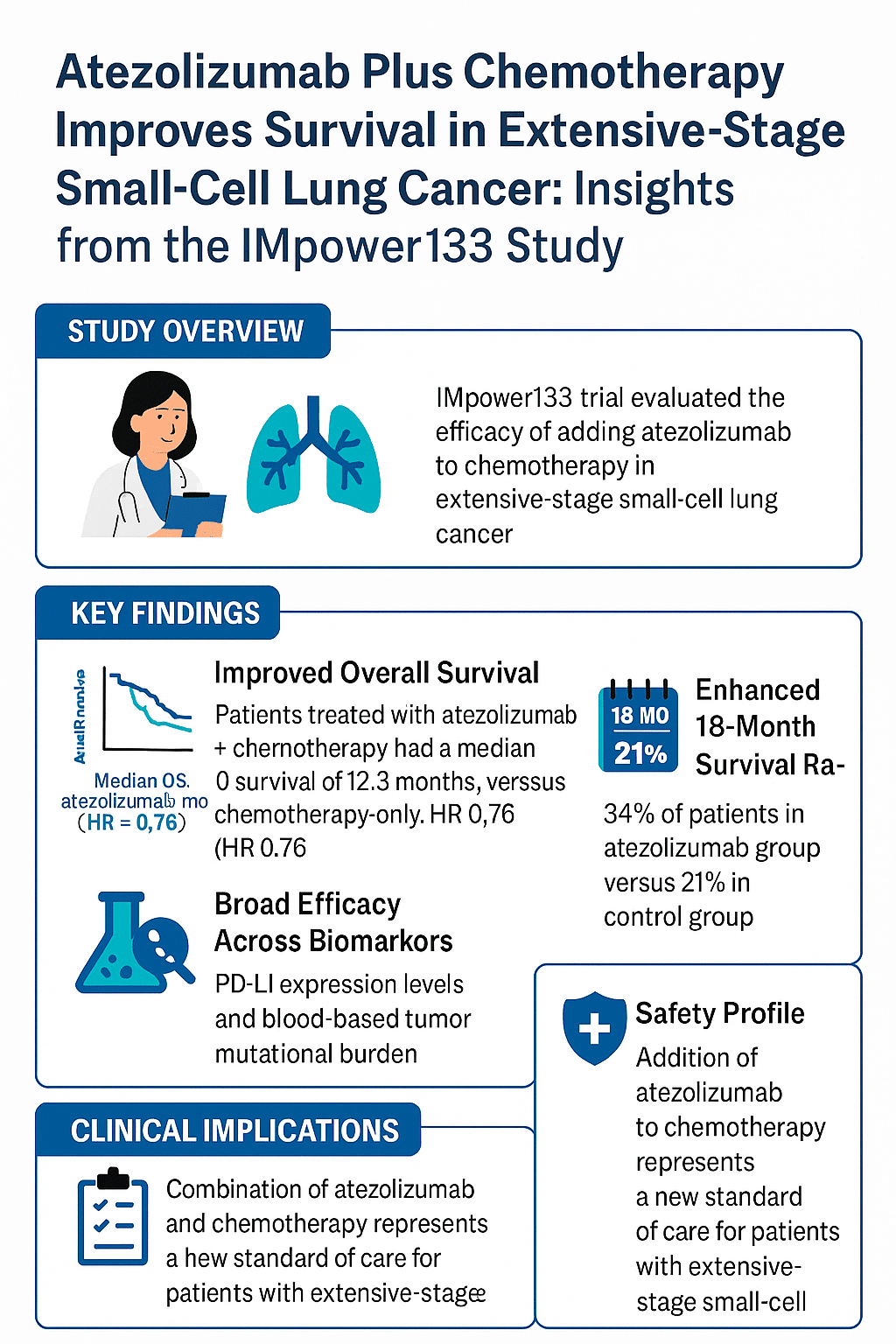

- Atezolizumab Plus Chemotherapy Improves Survival in Advanced-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Insights from the IMpower133 Study

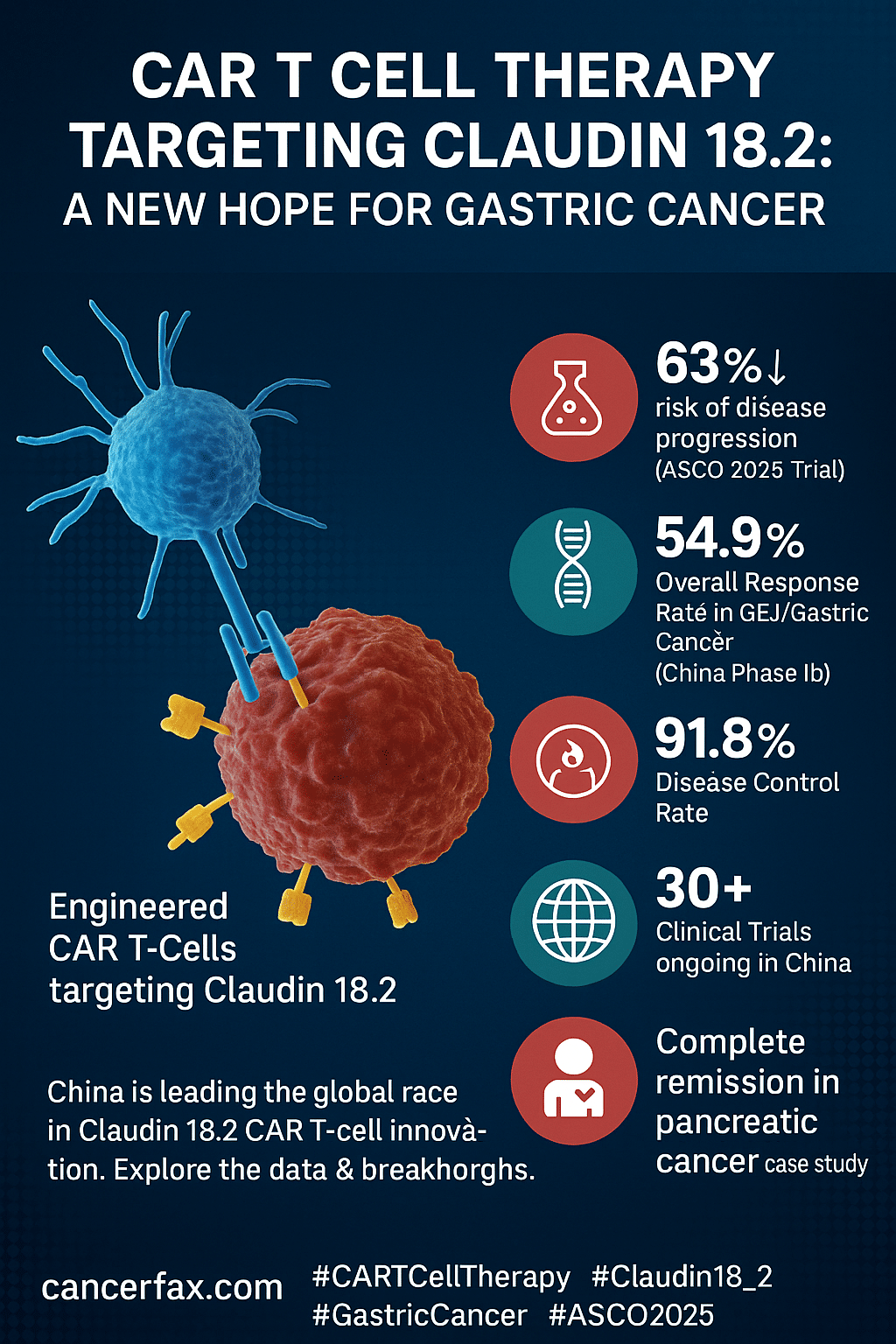

- Satri-cel CAR T-Cell Therapy: A New Era in Gastric Cancer Treatment

- AI & Technology (12)

- Aids cancer (4)

- Anal cancer (9)

- Appendix cancer (3)

- Basal cell carcinoma (1)

- Bile duct cancer (7)

- Biotech Innovations (19)

- Bladder cancer (12)

- Blood cancer (60)

- Bone cancer (12)

- Bone marrow transplant (47)

- Brain Cancer (1)

- Breakthrough Research (17)

- Breast Cancer (53)

- Cancer Guides (10)

- Cancer News and Updates (54)

- Cancer Treatment Abroad (286)

- Cancer treatment in China (316)

- Cancer Treatments (12)

- Cancer Types (5)

- Cancer Warriors (1)

- CAR T Protocols (2)

- CAR T-Cell therapy (135)

- Cervical cancer (40)

- Chemotherapy (55)

- Childhood cancer (2)

- Cholangiocarcinoma (3)

- Clinical trials (15)

- Colon cancer (96)

- Diagnosis & Staging (4)

- Doctors & Researchers (76)

- Drug Approvals (100)

- Drugs (80)

- Endometrial cancer (10)

- Esophageal cancer (15)

- Eye cancer (9)

- For Doctors and Researchers (12)

- Gall bladder cancer (3)

- Gastric cancer (29)

- Gene therapy (5)

- Glioblastoma (7)

- Glioma (10)

- Global Trial News (5)

- Gynecological cancer (2)

- Head and neck cancer (19)

- Hemato-Oncologist (1)

- Hematological Disorders (52)

- Hospital Reviews (3)

- How to Participate (6)

- Immunotherapy (34)

- Kidney cancer (10)

- Laryngeal cancer (1)

- Leukemia (49)

- Liver cancer (101)

- Lung cancer (82)

- Lymphoma (52)

- MDS (2)

- Melanoma (9)

- Merkel cell carcinoma (1)

- Mesothelioma (5)

- Myeloma (25)

- Myths vs Facts (5)

- Neuroblastoma (7)

- NK-Cell therapy (13)

- Nutrition (1)

- Ongoing Trials (11)

- Oral cancer (12)

- Ovarian Cancer (14)

- Pancreatic cancer (43)

- Paraganglioma (6)

- Patient Testimonials (1)

- Penile cancer (1)

- Prostrate cancer (11)

- Proton therapy (28)

- Radiotherapy (56)

- Recovery Tips (2)

- Rectal cancer (58)

- Research Insights (8)

- Sarcoma (14)

- Skin Cancer (13)

- Spine surgery (24)

- Stomach cancer (40)

- Success Stories (1)

- Surgery (102)

- Systemic mastocytosis (1)

- T Cell immunotherapy (7)

- Targeted therapy (9)

- Testicular cancer (5)

- Thoracic surgery (2)

- Throat cancer (6)

- Thyroid Cancer (15)

- Treatment Cost (1)

- Treatment in China (969)

- Treatment in India (1,273)

- Treatment in Israel (652)

- Treatment in Malaysia (425)

- Treatment in Singapore (321)

- Treatment in South Korea (305)

- Treatment in Thailand (291)

- Treatment in Turkey (272)

- Treatment Planning (151)

- Trial Results (2)

- Uncategorized (105)

- Urethral cancer (9)

- Urosurgery (14)

- Uterine cancer (4)

- Vaginal cancer (6)

- Vascular cancer (5)

- Vulvar cancer (1)

CancerFax is the most trusted online platform dedicated to connecting individuals facing advanced-stage cancer with groundbreaking cell therapies.

Send your medical reports and get a free analysis.

🌟 Join us in the fight against cancer! 🌟

Привет,

CancerFax — это самая надежная онлайн-платформа, призванная предоставить людям, столкнувшимся с раком на поздних стадиях, доступ к революционным клеточным методам лечения.

Отправьте свои медицинские заключения и получите бесплатный анализ.

🌟 Присоединяйтесь к нам в борьбе с раком! 🌟