CAR T- cell therapy for breast cancer is on the cards

March 2022: According to researchers at the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, adding a tiny chemical to a treatment process called chimeric antigen receptor-T (CAR-T) cell therapy can boost immune system T cells to successfully attack solid tumours like breast malignancies. The boost aids in the recruitment of more immune cells to the tumour location. Journal of Experimental Medicine published the findings. Apart from this study there are numerous ongoing clinical trials and seems CAR T-cell therapy for breast cancer is on cards and should be available very soon.

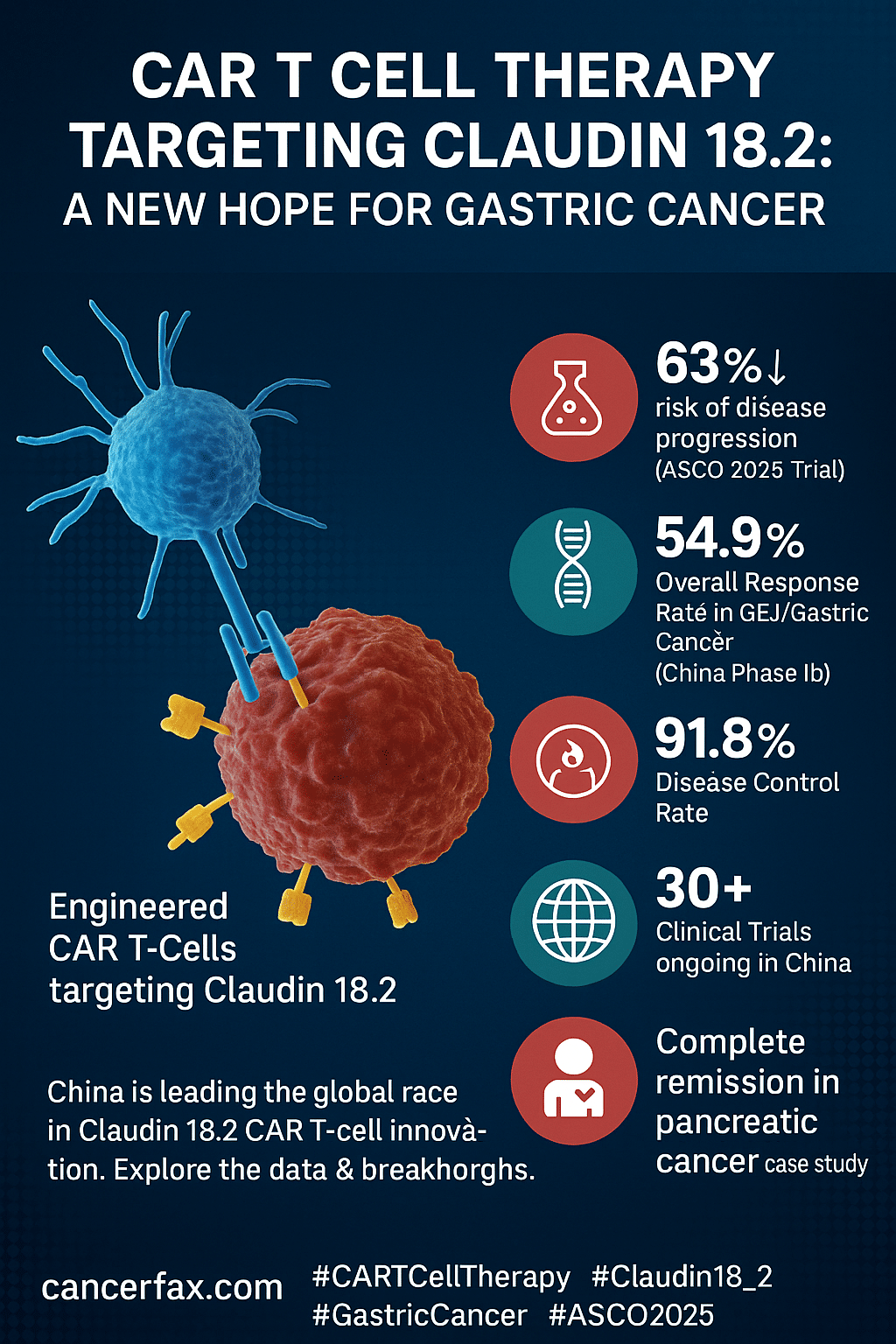

CAR-T immunotherapy, in which T cells are genetically modified to express chimeric antigen receptors (CARs), which then target surface proteins on cancer cells, has proven to be the most successful treatment for B-cell leukaemia and lymphoma patients. However, new research conducted in animal models suggests that CAR-T therapy could be beneficial against solid tumours as well.

“We know that CAR T cells are safe for patients with solid tumours, but they haven’t been able to cause significant tumour regression in the vast majority of people treated,” said Jonathan S. Serody, MD, the Elizabeth Thomas Professor of Medicine, Microbiology, and Immunology and director of UNC Lineberger’s Immunotherapy Program. We may now have a novel strategy to getting CAR T cells to work in solid tumours, which we believe might be a game-changer for cancer therapy targeting a large variety of diseases.

The paper’s corresponding author is Serody, and the first author is Nuo Xu, PhD, a former graduate student at UNC Lineberger and UNC School of Medicine.

T cells infused back into patients must be able to travel to the tumour location for CAR-T cell treatment to be effective. CAR T cells target bone marrow and other organs that make up the lymphatic system in individuals with non-solid malignancies such lymphomas. However, this is not always the case with solid tumours, such as breast cancer. Even if they do move to the tumour, the nature of the microenvironment around such tumours prevents them from persisting and expanding there, according to Serody.

Serody and his colleagues set out to find a way to steer the lab-expanded cells toward solid tumours. They concentrated on Th17 and Tc17 cells, which have been shown to stay longer in the microenvironment surrounding a tumour, owing to their superior survival capacities. They used two small compounds that can stimulate an immune response to promote the accumulation of Th17 and Tc17 cells around solid tumours: the stimulator of interferon genes (STING) agonists DMXAA and cGAMP.

Because it does not activate human STING, DMXAA, which worked well in the investigator’s mouse research, has not shown to be beneficial in human clinical trials. However, the other STING agonist, cGAMP, does activate human STING and has been shown to improve human immunity. It’s also effective in mice.

In Serody’s tests, mice injected with cGAMP showed increased T cell proliferation and migration to the tumour location. As a result, tumour growth was significantly slowed and survival was improved.

Dr. Nishant Mittal is a highly accomplished researcher with over 13 years of experience in the fields of cardiovascular biology and cancer research. His career is marked by significant contributions to stem cell biology, developmental biology, and innovative research techniques.

Research Highlights

Dr. Mittal's research has focused on several key areas:

1) Cardiovascular Development and Regeneration: He studied coronary vessel development and regeneration using zebrafish models1.

2) Cancer Biology: At Dartmouth College, he developed zebrafish models for studying tumor heterogeneity and clonal evolution in pancreatic cancer.

3) Developmental Biology: His doctoral work at Keio University involved identifying and characterizing medaka fish mutants with cardiovascular defects.

4) Stem Cell Research: He investigated the effects of folic acid on mouse embryonic stem cells and worked on cryopreservation techniques for hematopoietic stem cells.

Publications and Presentations

Dr. Mittal has authored several peer-reviewed publications in reputable journals such as Scientific Reports, Cardiovascular Research, and Disease Models & Mechanisms1. He has also presented his research at numerous international conferences, including the Stanford-Weill Cornell Cardiovascular Research Symposium and the Weinstein Cardiovascular Development Conference.

In summary, Dr. Nishant Mittal is a dedicated and accomplished researcher with a strong track record in cardiovascular and cancer biology, demonstrating expertise in various model systems and a commitment to advancing scientific knowledge through innovative research approaches.

- Comments Closed

- March 21st, 2022

Jonathan S. Serody, Journal of Experimental Medicine

CancerFax is the most trusted online platform dedicated to connecting individuals facing advanced-stage cancer with groundbreaking cell therapies.

Send your medical reports and get a free analysis.

🌟 Join us in the fight against cancer! 🌟

Привет,

CancerFax — это самая надежная онлайн-платформа, призванная предоставить людям, столкнувшимся с раком на поздних стадиях, доступ к революционным клеточным методам лечения.

Отправьте свои медицинские заключения и получите бесплатный анализ.

🌟 Присоединяйтесь к нам в борьбе с раком! 🌟